Company Stock In Your 401(k)? Don’t Forget To Elect NUA

If you’re retiring or leaving your job and have company stock in your 401(k), understanding NUA (Net Unrealized Appreciation) could save you thousands in taxes. Many miss this valuable opportunity by rolling everything into an IRA without considering the tax implications. Our latest article breaks down how NUA works, common tax mistakes, and when choosing NUA makes sense. Learn how factors like your age, retirement timeline, and stock performance play a role. Don’t overlook this strategy if your company stock has grown significantly in value—it could make a big difference in your retirement savings.

For employees with company stock as an investment holding within their 401(k) accounts, there is a special distribution rule available that provides significant tax benefits called “NUA”, which stands for Net Unrealized Appreciation. The NUA option becomes available to employees who have either retired or terminated their employment with a company and are in the process of rolling over their 401(k) balances to an IRA. The purpose of this article is to help employees understand:

How does the NUA 401(k) distribution option work?

What are the tax benefits of electing NUA?

The immediate tax event that is triggered with an NUA election

What situations should NUA be elected?

What situations should NUA be AVOIDED?

Special estate tax rules for NUA shares

The Common Rollover Mistake

For employees who have company stock in their 401(k) and do not receive proper guidance, they can easily miss the window to make the NUA election, which can cost them thousands of dollars in additional taxes in their retirement years. When employees leave a company, it’s common for the employee to open a Rollover IRA and process a direct rollover of their entire balance in their 401(k) to their IRA to avoid triggering an immediate tax event as they move their retirement savings away from their former employer.

Example: Tim retires from Company ABC and has a $500,000 balance in that 401(k) plan; $200,000 of the $500,000 is invested in ABC company stock. He sets up a traditional IRA, calls the 401(k) provider, and requests that they process a direct rollover of the full $500,000 balance from his 401K to his IRA. The 401(k) platform processes the rollover, and Tim deposits the $500,000 to his IRA with no taxes being triggered. Then, Tim begins taking distributions from his IRA to supplement his income in retirement. On the surface, everything seems perfectly fine with this scenario. However, Tim may have completely missed a huge tax-saving opportunity by failing to request NUA treatment of his company stock within his 401(k) account.

How Does NUA Work?

When an employee has company stock in their 401(k) account and they go to take a distribution/rollover from their 401(k) after they leave employment with the company, they may be able to elect NUA treatment of the portion of their 401(k) that is invested in company stock. But what does NUA treatment mean? When an employee processes a rollover from their pre-tax 401(k) balance to their Rollover IRA, and then takes distributions from their IRA in the future, they have to pay ordinary income tax on all distributions taken from the IRA account. However, prior to requesting a full rollover of their 401(k) balance to their IRA, an employee with company stock in their 401(k) account can make an NUA election, which allows the appreciation in the stock within the 401(k) account to be taxed at long-term capital gains rates in the future as opposed to ordinary income tax rates which may be higher.

But employees must be aware that by electing NUA, it triggers an immediate tax event for the employee.

Here is how NUA works as an example. Sue has a 401(k) account with Company XYZ. The total balance of Sue’s 401(k) is $800,000, but $400,000 of the $800,000 balance is invested in XYZ company stock that Sue has accumulated over the past 20 years with the company. The cost basis of Sue’s $400,000 in company stock within the 401(k) is $50,000, so over that 20-year period, the company stock has gained $350,000 in value.

When Sue retires, instead of rolling over the full $800,000 balance to her Rollover IRA, she makes an NUA election. The NUA election will send the $400,000 in company stock within her 401(k) account to an after-tax brokerage account in Sue’s name as opposed to a Rollover IRA account. When that happens, Sue has to pay ordinary income tax, not on the full $400,000 value of the stock, but on the $50,000 cost basis amount of the company stock. The $350,000 in “unrealized gain” in the company stock is now sitting in Sue’s brokerage account, and when she sells the stock, she receives long-term capital gain treatment of the $350,000 gain, as opposed to paying ordinary income tax on the $350,000 gain if it was rolled over to her IRA.

But what happens to the rest of Sue’s 401(k) balance that was not invested in company stock? The non-company stock portion of Sue’s 401(k) account can be rolled over to a Rollover IRA and it’s a 100% tax-free event. She just pays ordinary income tax on future distributions from the IRA account.

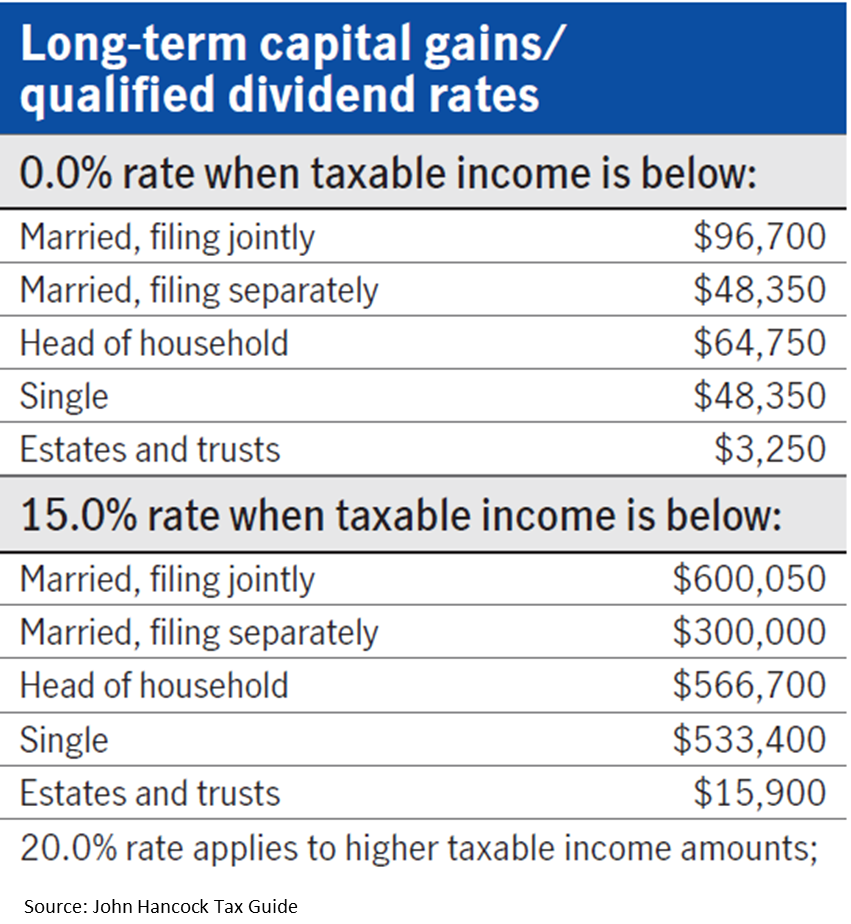

NUA – Long-Term Capital Gains Rates

Depending on Sue’s income level in retirement, her federal long-term capital gains rate may be 0%, 15%, or 20%, which may be lower than if she had realized the IRA distribution at ordinary income tax rates. Here is a quick chart that illustrates the 2025 long-term capital gains rates by filing status and income level:

NUA Triggers A Tax Event

Now let’s go back and review the tax event that was triggered when Sue requested the $400,000 transfer of her company stock from the 401(k) to her brokerage account. Again, when the NUA is processed, she only has to pay ordinary income tax on the cost basis amount of the stock, so in Sue’s case, in the year the NUA distribution takes place, she would have to report an additional $50,000 in taxable income. The tax liability generated could either be paid with her personal cash reserve or she could liquidate some of the company stock in her after-tax brokerage account to pay the taxes.

Timing of the NUA Distribution

There is a tax strategy associated with the timing of requesting the NUA distribution. If someone works for a company until September and then retires, they already have 9 months' worth of income in that tax year. In this case, it may be beneficial to process the rollover from the 401(k) with the NUA to the brokerage account the following tax year, when the individual’s W-2 income is completely off the table, so the taxable cost basis associated with the NUA election is potentially taxed at a lower rate since there is no W2 income the following year.

The Employee’s Age Matters for NUA

Because the cost basis of the company stock is treated like a cash distribution, if an employee takes an NUA distribution before age 55 and has already left the company, the cost basis would be subject to ordinary income tax and the 10% early withdrawal penalty.

NUA – Age 55 Exception To The 10% Early Withdrawal Penalty

Why age 55 and not 59½? Qualified retirement plans (401(k), 403(b), 457(b) plans) have a special exception to the under age 59½ 10% early withdrawal penalty. If you terminate employment with the company AFTER reaching age 55 and you take a cash distribution or NUA directly from the 401(k) plan, the employee is no longer subject to the 10% early withdrawal penalty. But an employee who terminates employment at age 54 and requests the NUA distribution at age 55 would still get hit with the 10% penalty because they did not separate from service AFTER reaching age 55.

The cost basis associated with the NUA distribution is treated the same as a regular cash distribution from a 401(k) plan.

When Electing NUA Makes Sense

There are certain situations where making the NUA election makes sense, and there are situations where it should be avoided. We will start off by reviewing the common situations where electing NUA makes sense in lieu of rolling over the entire balance to an IRA.

Large Unrealized Gain In The Company Stock

In order for the NUA election to make sense, there typically has to be a large unrealized gain built up in the company stock within the 401(k) plan. Said another way, the company stock has to have performed well within the 401(k) account. If the value of the company stock in an employee's 401(k) account is $200,000 and the cost basis is $170,000, if that employee elects an NUA and then transfers the $200,000 in stock to their brokerage account, it’s going to trigger a $170,000 immediate tax event and only $30,000 would receive long-term capital gains treatment. In this case, it’s probably not worth the tax hit.

In the example with Sue, she only had to pay ordinary income tax on $50,000 of the $400,000 in company stock, so the NUA would make more sense in her situation because she is shifting $350,000 to long-term capital gains treatment.

Ordinary Income Tax vs Long Term Capital Gains Rates

For NUA to make sense, it’s a race between what tax rate someone would pay if the money were distributed from a Rollover IRA and distributed at ordinary income tax rates versus the long-term capital gains tax rate if NUA is elected. Under current tax law, the federal tax rate jumps from 12% to 22% at $96,950 for a joint tax filer. On the surface it would seem that someone with under $96,950 in income might be better off rolling over the balance to an IRA and paying ordinary income tax rates at 12% instead of the long-term capital gains rate of 15%. However, if you look at the long-term capital gains tax rates in the table earlier in the article, if in 2025 a joint filer has income below $96,700, the long-term capital gains rate is 0%, and a 0% tax rate always wins.

Time Horizon Matters

An employee's time horizon to retirement also factors into the NUA decision. If an employee leaves a company at age 40, not only would they have to pay taxes and the 10% penalty on the cost basis of the NUA distribution, but by moving the company stock to a taxable brokerage account, they are losing the tax deferred accumulation benefit associated with the Rollover IRA for the next 19+ years. Since the brokerage account is a taxable account, the owner of the account has to pay taxes every year on dividends, interest, and realized gains produced by the brokerage account. If the company stock is liquidated and the full 401(k) balance is rolled over to an IRA, all of the investment income avoids immediate taxation and continues to accumulate within the IRA account. For taxpayers in higher tax brackets, this may have its advantages.

There are a lot of factors in the NUA decision, but in general, the shorter the timeline to when distributions will begin from retirement savings, the more it favors NUA; the longer the time horizon to retirement, the less it favors NUA over the benefits of continued tax deferred accumulation in a Rollover IRA account.

Reduce Future RMDs

For individuals who have a majority of their assets in pre-tax retirement accounts, like 401(k) and IRA accounts, and are fortunate enough to not need to take large distributions from those accounts in retirement because they have other sources of income, eventually when those individuals reach RMD age (73 or 75), the IRS is going to force them to start taking large taxable distributions out of their pre-tax retirement accounts.

For an individual in this situation, electing NUA can be an attractive option. Instead of their full 401(k) balance ending up in a Rollover IRA with a future RMD requirement, the company stock is sent to a brokerage account that does not require RMDs.

Estate Planning – No Step-Up In Cost Basis for NUA

Here is a little-known estate planning fact about NUA elections. Normally, when you have unrealized gains in a brokerage account and the owner of the account passes away, the beneficiaries of the estate receive a step-up in cost basis, which eliminates the taxable gain if the beneficiaries were to sell the stock. For individuals that elect NUA from a 401(k) account, there is a special rule that states if shares are deposited into a brokerage account as a result of an NUA election, the remaining portion of the NUA will be considered “income with respect of the decedent”, meaning the beneficiaries of the estate will have to pay long-term capital gains when they eventually sell those shares.

I’m not sure how this is tracked because when you move shares into a brokerage account that has NUA, if the shares continue to appreciate in value, and shares are bought and sold throughout the decedent’s lifetime, how do you determine which portion of the remaining unrealized gain was from the NUA election and which portion represents unrealized gains post NUA? A wonderful question for your tax professional if you end up in this situation.

When To Avoid NUA

As part of the analysis above, I highlighted a number of situations where an NUA election might not make sense, but a quick hit list is:

Company stock has not performed well in 401(k) account – high cost basis

High tax rate assessed on the cost basis amount during the year of NUA election

Employee under age 55 or 59½, potentially triggering early withdrawal penalty

Long time horizon to retirement (loss of tax deferred accumulation)

Ordinary tax rate lower or similar to long-term capital gains rate

About Michael……...

Hi, I’m Michael Ruger. I’m the managing partner of Greenbush Financial Group and the creator of the nationally recognized Money Smart Board blog . I created the blog because there are a lot of events in life that require important financial decisions. The goal is to help our readers avoid big financial missteps, discover financial solutions that they were not aware of, and to optimize their financial future.

Do I Have To Pay Tax On A House That I Inherited?

The tax rules are different depending on the type of assets that you inherit. If you inherit a house, you may or may not have a tax liability when you go to sell it. This will largely depend on whose name was on the deed when the house was passed to you. There are also special exceptions that come into play if the house is owned by a trust, or if it was gifted

Do I Have To Pay Tax On A House That I Inherited?

The tax rules are different depending on the type of assets that you inherit. If you inherit a house, you may or may not have a tax liability when you go to sell it. This will largely depend on whose name was on the deed when the house was passed to you. There are also special exceptions that come into play if the house is owned by a trust, or if it was gifted with the kids prior to their parents passing away. On the bright side, with some advanced planning, heirs can often times avoid having to pay tax on real estate assets when they pass to them as an inheritance.

Step-up In Basis

Many assets that are included in the decedent’s estate receive what’s called a step-up in basis. As with any asset that is not held in a retirement account, you must be able to identify the “cost basis”, or in other words, what you originally paid for it. Then when you eventually sell that asset, you don’t pay tax on the cost basis, but you pay tax on the gain.

Example: You buy a rental property for $200,000 and 10 years later you sell that rental property for $300,000. When you sell it, $200,000 is returned to you tax free and you pay long-term capital gains tax on the $100,000 gain.

Inheritance Example: Now let’s look at how the step-up works. Your parents bought their house 30 years ago for $100,000 and the house is now worth $300,000. When your parents pass away and you inherit the house, the house receives a step-up in basis to the fair market value of the house as of the date of death. This means that when you inherit the house, your cost basis will be $300,000 and not the $100,000 that they paid for it. Therefore, if you sell the house the next day for $300,000, you receive that money 100% tax-free due to the step-up in basis.

Appreciation After Date of Death

Let’s build on the example above. There are additional tax considerations if you inherit a house and continue to hold it as an investment and then sell it at a later date. While you receive the step-up in basis as of the date of death, the appreciation that occurs on that asset between the date of death and when you sell it is going to be taxable to you.

Example: Your parents passed away June 2019 and at that time their house is worth $300,000. The house receives the step-up in basis to $300,000. However, lets say this time you rent the house or don’t sell it until September 2020. When you sell the house in September 2020 for $350,000, you will receive the $300,000 tax-free due to the step-up in basis, but you’ll have to pay capital gains tax on the $50,000 gain that occurred between date of death and when you sold house.

Caution: Gifting The House To The Kids

In an effort to protect the house from the risk of a long-term event, sometimes individuals will gift their house to their kids while they are still alive. Some see this as a way to remove themselves from the ownership of their house to start the five-year Medicaid look back period, however, there is a tax disaster waiting for you with the strategy.

When you gift an asset to someone, they inherit your cost basis in that asset, so when you pass away, that asset does not receive a step-up in basis because you don’t own it and it’s not part of your estate.

Example: Your parents change the deed on the house to you and your siblings while they’re still alive to protect assets from a possible nursing home event. They bought the house 30 years ago for $100,000, and when they pass away it’s worth $300,000. Since they gifted the assets to the kids while they were still alive, the house does not receive a step-up in basis when they pass away, and the cost basis on the house when the kids sell it is $100,000; in other words, the kids will have to pay tax on the $200,000 gain in the property. Based on the long-term capital gains rates and possible state income tax, when the children sell the house, they may have a tax bill of $44,000 or more which could have been completely avoided with better advanced planning.

How To Avoid Paying Capital Gains Tax On Inherited Property

There are ways to both protect the house from a long-term event and still receive the step-up in basis when the current owners pass away. This process involves setting up an irrevocable trust to own the house which then protects the house from a long-term event as long as it’s held in the trust for at least five years.

Now, we do have to get technical for a second. When an asset is owned by an irrevocable trust, it is technically removed from your estate. Most assets that are not included in your estate when you pass do not receive a step-up in basis; however, if the estate attorney that drafts the trust document puts the correct language within the trust, it allows you to protect the assets from a long-term event and receive a step-up in basis when the owners of the house pass away.

For this reason, it’s very important to work with an attorney that is experienced in handling trusts and estates, not a generalist. It only takes a few missing sentences from that document that can make the difference between getting that asset tax free or having a huge tax bill when you go to sell the house.

Establishing this trust can sometimes cost between $3,000 and $6,000. But by paying this amount upfront and doing the advance planning, you could save your heirs 10 times that amount by avoiding a big tax bill when they inherit the house.

Making The House Your Primary

In the case that the house is gifted to the children prior to the parents passing away and the house is not awarded the step-up in basis, there is an advance tax planning strategy if the conditions are right to avoid the big tax bill. If one of the children would be interested in making their parent’s house their primary residence for two years, then they are then eligible for either the $250,000 or $500,000 capital gains exclusion.

According to current tax law, if the house you live in has been your primary residence for two of the previous five years, when you go to sell the house you are allowed to exclude $250,000 worth of gain for single filers and $500,000 worth of gain for married filing joint. This advanced tax strategy is more easily executed when there is a single heir and can get a little more complex when there are multiple heirs.

About Michael……...

Hi, I’m Michael Ruger. I’m the managing partner of Greenbush Financial Group and the creator of the nationally recognized Money Smart Board blog . I created the blog because there are a lot of events in life that require important financial decisions. The goal is to help our readers avoid big financial missteps, discover financial solutions that they were not aware of, and to optimize their financial future.